Stretching is In Your Brain: A New Paradigm of Flexibility & Yoga (Part 1)

Update 1/10/22: I originally wrote this article in January of 2015 (7 years ago at the time of this update!) Since that time, I’ve learned a lot more about the science of stretching and I’ve updated my perspective on it. I can’t really endorse this older article anymore because it doesn’t represent my approach today. For a full view of my current science-based approach (based on the scientific literature on stretching through 2021), see these resources:

Podcast episode: Stretching Myths & Stretching Facts

Continuing ed course: Stretching Science 101

This blog post was first sent to Jenni’s email list as an email newsletter. Sign up for the JRY email newsletter here!

In yoga, we tend to place a lot of emphasis on stretching as a means toward more flexibility. But what actually happens in our body when we stretch? Most of us envision our bodies as consisting of play-doh like tissues that we pull on and make longer through stretching, but new science is revealing to us a model of stretching that is much more complex, dynamic, and fascinating than what has previously been imagined. And it turns out that thinking of our bodies in this older “play-doh” like version may be counterproductive and can lead to a number of injuries and structural problems resulting from our yoga practice. In order to keep our wonderful yoga tradition evolving and current, it’s important that we understand this new and fascinating science of stretching and any implications it might offer for our practice and teaching.

A NEW PARADIGM OF FLEXIBILITY

Biomechanics-based Restorative Exercise™ teaches a lot of new and eye-opening information about stretching and flexibility that isn’t yet common knowledge in the yoga world. Additionally, the wonderful yoga teacher Jules Mitchell is on a mission to educate the yoga community about the science of stretching. Her recently-completed master’s thesis in exercise science is a comprehensive literature review of the most current scientific research on stretching to date, and it’s full of an abundance of important information for yogis.

Utilizing the innovative knowledge that these resources offer, let’s examine some of our current beliefs about stretching and introduce some helpful ways we can begin to update these beliefs to reflect the newest scientific word on the street.

WHAT WE THINK HAPPENS WHEN WE STRETCH

Most people think of their muscles as being either “long” or “short”, and that during a stretch, they are targeting their “short” muscles by physically “lengthening” or “loosening” them. In this stretching paradigm, our muscles are mold-able tissues like taffy or play-doh which we can form into a shape of our choosing by simply pulling or pushing on them. For example, when we fold forward into paschimottanasana (seated forward fold), we tend to imagine that our hamstrings are physically growing longer in that moment of our stretch in the same way that taffy would grow longer if we tugged on both of its ends for awhile. We imagine that when we release paschimottanasana, our hamstrings remain just a bit longer than they were before we did the stretch. And we also imagine that the longer and deeper we hold a pose like paschimottanasana, the longer and looser our hamstrings become.

This stretching paradigm is what most of us were taught in our yoga classes, workshops, and teacher trainings. It’s completely understandable that we might see the body as working like this, but new research is revealing a very different version of the biomechanics of stretching.

THE NEW SCIENCE OF WHAT HAPPENS WHEN WE STRETCH

We all know that when we stretch, we experience a feeling of “tightness” at our end range of motion - a sensation that limits us from moving any deeper into the stretch. We have traditionally defined this “tight” sensation as the result of having reached the end length of the muscle(s) we’re stretching. In other words, we pulled on the ends of our muscle until we reached its maximum physical length, and once we hit that boundary, the stretch stopped and we felt the “tightness”. With enough stretching, we could increase the length of our muscle and therefore move further into our stretch with time.

The king of flexibility.

But we now understand that increasing our flexibility has much less to do with the physical length of our muscle tissue, and much more to do with the part of our body that controls and moves our muscles: the nervous system. Our brain and spinal cord, which make up our central nervous system (CNS), are constantly monitoring the state of our body. One of the main imperatives of the CNS to keep our body where it perceives it is safe. Normal movements that we make throughout our day are considered safe by the CNS because it knows and trusts them. But on the other hand, our CNS is not familiar with ranges of motion that we never move into, so it’s much less likely to consider those places safe. When we stretch, if we move into a place that the CNS isn’t familiar with, our nervous system will likely end our stretch by creating a sensation of discomfort at the end range of motion it considers safe.

For example, if you happen to work on your computer for 8 solid hours a day (and if you don’t take frequent intermittent stretch breaks for your shoulders - hint hint :) ), the CNS becomes very familiar with the arms-forward position that you use while typing and considers that range safe. Then later, if you decide to do a chest stretch in which you take your arm out to the side and then behind you, the CNS doesn’t feel that that movement is safe because you so rarely go there, so it will limit your range very early on in the stretch.

A major takeaway from this new flexibility paradigm is that when we increase our range of motion through stretching, it isn’t because we pulled on our tissues and made them longer. It’s because we visited the edge of our stretch (also called stretch “tolerance”) enough times that our CNS started to feel comfortable there and it began to allow us to move deeper into that range.

OKAY, I THINK I’M STARTING TO GET IT, BUT WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

It’s definitely interesting and more scientifically accurate to understand this previously-overlooked role that our nervous system plays in flexibility. But whether it’s your nervous system or the physical length of your muscles limiting you in a stretch, why does it matter? Isn’t a stretch a stretch, regardless of the mechanism behind it?

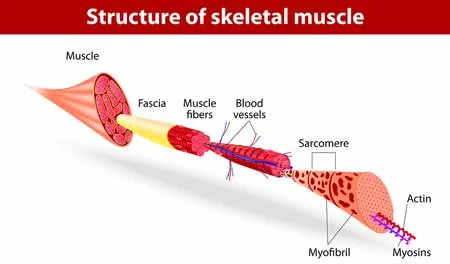

That’s a great question - I’m so glad you asked! The main answer has to do with what tissues are being targeted when we stretch. We often think and talk about stretching our muscles in our yoga poses (i.e. paschimottanasana stretches our “hamstrings”), but in truth our muscles are surrounded by, interwoven with, and inseparable from our fascia. Our fascia is our incredible body-wide web of connective tissue that is literally everywhere inside of us, and it includes our tendons and ligaments. Muscles and fascia are two distinct tissues with different properties, but both are affected when we stretch. And how we choose to stretch, which is based on whether we believe that we’re physically lengthening our muscles (old paradigm) or increasing our nervous system’s tolerance for the stretch (new paradigm), determines how our fascia will be affected during the movement. (Preview for Part 2 of this post: if we’re going with the older “pulling on our tissues like play-doh" paradigm, we’ll feel more drawn to stretching deeper and harder in our poses, which is much more likely to simply damage our tissues than give us the flexibility we seek.)

I’ll elaborate more on this and other important topics, like how we might choose to apply this new information to our yoga practice and teaching, in my next blog post. Stay tuned, guys! And in the meantime, if you’re interested in further reading, check out this awesome article by Jules Mitchell (written for a pretty science-oriented reader). See you for Part 2 soon!