Physical Touch in Yoga: Do Teachers & Students Agree?

This blog post was first sent to Jenni’s email list as an email newsletter. Sign up for the JRY email newsletter here!

by Jenni Rawlings & Travis Pollen

Introduction

The question of whether or not yoga teachers should offer physical touch to their students is currently a hotly-debated topic in the yoga community. Touch in the form of physical adjustments and physical assists has been an integral part of many styles of yoga classes for decades. But in more recent times, concerns about effectiveness, consent, and trauma have arisen that have caused many in the yoga community to question the appropriateness of physical touch in yoga. At the same time, many other yoga practitioners continue to support what they see as the inherent value in the offering of touch in yoga classes.

In an effort to highlight the wide spectrum of views on this topic, we conducted a written interview series in January 2020: “5 Influential Yogis Weigh in on Yoga Adjustments: When, Why, and Whether to Give Them.” The response and discussions facilitated by this piece were revealing and further demonstrated a lack of consensus on this important topic in the yoga world.

One aspect of the yoga adjustments debate that we have not seen investigated is the question of whether yoga teachers and yoga students tend to agree or disagree on physical touch and consent practices in yoga. An understanding of where these two groups overlap in their views and where they diverge would be helpful in informing the overall discussion about physical touch in yoga.

Do yoga students tend to prefer being touched or not, and how do they prefer to establish consent? Do teachers tend to offer touch to their students or not, and what methods do they choose in establishing consent? How often do the views between these groups overlap? Where are there disconnects?

With the intention of further contributing to this conversation, we set out to investigate whether yoga students and yoga teachers agree in their views on physical touch and consent practices in yoga via a survey. Below, we’ll describe how we conducted the survey, who the 931 (!) respondents were, what we found, what we think it means for teachers and for students, and what new questions our findings raise.

What We Did

In January 2020, we sent out a short anonymous survey to Jenni’s email list and social media followers. The survey was subsequently shared on social media, resulting in a mix of respondents who found the survey link through Jenni and through colleagues.

Teachers filled out one version of the survey; students filled out another. If a respondent identified as both a teacher and a student (as many teachers do) we asked them to complete the survey as a teacher.

We asked the teachers the following questions about physical touch in their teaching practices:

Do you provide physical touch in the yoga classes you teach?

How do you establish consent to touch with your students?

For which reason(s) do you NOT provide physical touch during class?

For which reason(s) do you provide physical touch during class?

We asked the students analogous questions about their preferences for physical touch:

Do you like/dislike to receive physical touch from your teacher during yoga class?

How do you prefer to establish consent to touch with your teacher?

For which reason(s) do you prefer NOT to receive physical touch during class?

For which reason(s) do you enjoy receiving physical touch during class?

For each of the questions, we provided an array of possible responses as well as the option to write in an answer (should none of the options we provided apply). For questions 2-4, respondents were free to check all responses that applied.

To get a better sense of who was filling out the survey, we also asked for the respondents’ gender, age, location, race, years and frequency of teaching/practicing, primary style of yoga, and primary setting. Finally, we asked whom they heard about the survey from.

To determine whether there were differences between the teachers’ and students’ responses to questions 2-4, we ran a stat called a Chi-squared test. (If you’re curious about the details of the statistics, we’d be happy to share more; just let us know.)

At the end of the survey, we also provided a space for respondents to share anything else they wanted us to know. We used these open-ended responses to help interpret our numerical findings.

Description of Respondents

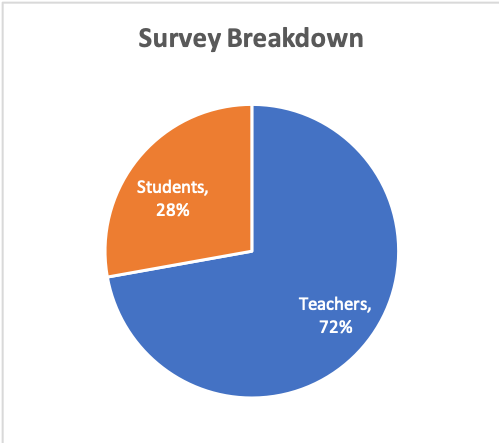

Number of responses: 931 (72% teachers, 28% students)

Gender: Female (92%) , Male (7%), Non-binary/third gender (1%)

Age: Average = 41; Range = 21 to 75

Location: North America (75%), Europe (17%), Asia (3%), Australia (3%), South America (1%), Africa (1%)

Race: White (86%), Prefer not to answer (7%), Asian (4%), Black or African American (2%), American Indian or Alaska Native (1%), Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (0.2%), Other (3%)

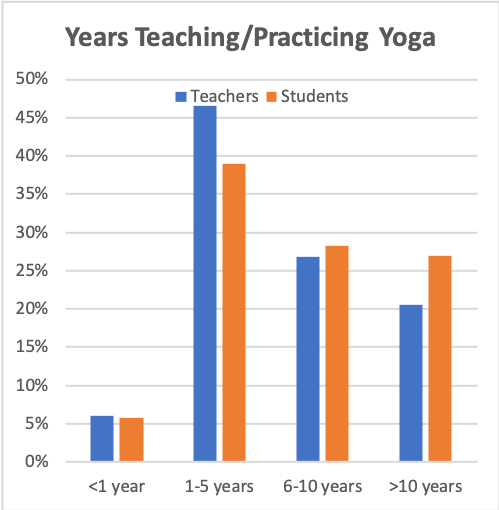

Years teaching/practicing yoga: Average = 5; Range = less than a year to 50 years

Yoga frequency: 5 or more times a week (34%), 2-4 times a week (41%), Once a week (12%), Less than once a week (13%)

Primary yoga style: Vinyasa (40%), Hatha (23%), Yin (4%), Restorative (4%), Therapeutic (4%), Ashtanga (4%), Iyengar (3%), Not sure (3%), Bikram/hot yoga (2%), Anusara (1%), Kundalini (0.4%), Other (13%)

Primary setting: Yoga studio (67%), Gym or other fitness center (12%), Private (7%), Corporate classes (1%), Other (13%)

What We Found

Teacher Practices and Student Preferences

The first question we asked students was whether they like or dislike receiving physical touch from their teacher during yoga class. About 3 in 4 of the 259 students we surveyed reported liking or strongly liking to receive touch. Conversely, less than 1 in 10 students disliked or strongly disliked receiving touch. The rest of the students (about 2 in 5) were neutral.

These findings contrasted considerably with teachers’ practices. Nearly half of the 672 teachers surveyed reported that they rarely or never provide physical touch in their yoga classes. Meanwhile, about 1 in 5 teachers reported that they always or often provide physical touch. The remaining 35% of teachers provide touch sometimes.

Establishing Consent

We asked teachers how they establish consent to touch students, and we asked students how they prefer to provide consent. The responses varied widely for both teachers and students, with no clear consensus among either group.

The strategies the teachers reported most frequently were (1) a verbal check-in before every touch (40%), (2) a verbal check-in the first time a student takes their class (27%), and (3) a non-verbal signal during class. Only about 1 in 9 teachers reported using consent cards. Finally, 6% of teachers reported that they don’t ask for consent to touch, as they believe it’s implied in a yoga setting.

The students’ top responses were (1) a verbal check-in the first time they take a class with a teacher (38%), (2) a non-verbal sign during class (34%), and (3) consent cards (21%). Less than 1 in 5 students preferred a verbal check-in before every touch, which was the teachers’ most frequently reported strategy. Almost the same proportion of students (about 1 in 5) actually preferred that their teachers not ask for consent, considering it implied.

Reasons for Touch

We asked teachers to indicate the reasons they provide physical touch, and we asked students to indicate the reasons they enjoy receiving physical touch.

An equal proportion of the teachers and students selected the following two reasons:

Over 7 in 10 respondents in both groups cited bringing awareness to an area of the body the student is having trouble sensing as a reason for touch.

Nearly half of each group reported helping to relax as a reason for touch.

However, response rates differed substantially on all of the other reasons for touch:

Over 7 in 10 students reported wanting physical touch to correct a pose. Conversely, only about 1 in 4 teachers offer such an adjustment.

Over 3 in 5 students enjoy receiving touch to deepen a pose or stretch, but only about 1 in 5 teachers provide touch in that form.

Just over half of students enjoy physical touch to help them achieve a pose they wouldn’t otherwise be able to (e.g. binding hands behind back, holding a handstand, etc.), but again only about 1 in 5 teachers provide touch in that form.

Almost 2 in 5 students enjoy being touched simply because they appreciate touch. Only about 1 in 5 teachers provide touch for that reason.

About half of students enjoy touch to help them avoid injury, whereas less than 2 in 5 teachers indicated injury prevention as a reason for touch.

Reasons Against Touch

Finally, we asked teachers for the reasons they do not provide physical touch, and we asked students for the reasons they prefer not to receive it.

At least half of the teachers surveyed reported the following three reasons: (1) they are sensitive to the possibility of trauma being an issue for their students (72%), (2) they want students to discover poses for themselves and not rely on the teacher (61%), and (3) they are afraid of the possibility of injuring their students through touch (50%).

The next most frequent responses were “verbal cues and visual demonstrations are superior to physical touch” and “consent is too tricky to establish; it’s easier just not to touch” (26% each). 1 in 5 teachers cited touch as a distraction from the student’s practice.

Meanwhile, more than half of the students (53%) surveyed reported that there was no reason why they prefer not to be touched. The reason with the highest response rate was fear of injury from touch, although only about 1 in 5 students pointed to this as a reason. Only 12% of students reported a history of trauma, only 12% found touch distracting, only 7% wanted to discover poses for themselves instead, and only 5% thought verbal cues and visual demonstrations are superior to touch.

Interestingly, almost 1 in 5 teachers reported not feeling qualified to provide touch, yet less than 1 in 10 students viewed their teacher as unqualified in this regard.

Implications for Students and Teachers

Teacher Practices and Student Preferences

Overall, the results of this survey suggest that yoga teacher practices and yoga student preferences regarding physical touch and consent are at odds (with a few notable exceptions). 74% of yoga students like receiving physical touch in yoga, but only 19% of yoga teachers offer touch “always” or “often.” Only 10% of students dislike being touched, yet nearly half of teachers offer touch “rarely” or “never.”

Reasons for Touch

Both teachers and students tend to agree that in an environment where touch is offered, two good reasons to touch students are “to help bring awareness to an area of the body a student is having trouble sensing” and “to help the student relax.” The overlap between the two groups on these reasons suggests that teachers who touch for body awareness and relaxation reasons should feel justified in continuing to do so.

For the purposes of facilitating relaxation, touch offered during savasana (final relaxation pose) was the most commonly mentioned example in our survey. According to respondents, this could take the form of a “light touch to the shins,” a squeeze or massage of the feet, and/or shoulder and head massages.

In fact, many teachers reported providing no physical touch throughout the entirety of their class, yet still offering savasana adjustments to those students who opt in to receiving them. Savasana seems to be a key time in a yoga class where physical touch for the sake of relaxation is largely agreed upon as appropriate and effective. And because relaxation and stress reduction is a common reason for students to attend yoga classes, savasana adjustments may be one means that teachers can help facilitate this goal for students.

As for the other five possible reasons for touch besides awareness and relaxation, students wanted touch more for each reason than teachers reported providing it. At least half of the students cited 6 of the 7 answers we provided as reasons they prefer to receive touch. This finding reflects the responses to Question #1 – that more students wanted touch than teachers provide it.

Interestingly, yoga students were almost three times more likely to enjoy receiving physical adjustments for the purpose of correcting poses than yoga teachers were likely to give such “corrective” adjustments. Perhaps this speaks to a difference between the way teachers and students approach the notion of a “correct” pose? There is a growing trend in the yoga world today in which teachers are preferring to teach poses in a more exploratory manner versus a more correct/incorrect one. However, many students – particularly those who are new to the practice – have the desire to make sure they are performing their poses “correctly.”

Even though many teachers might prefer an exploratory approach to teaching poses these days, there may still be value (at least from the perspective of students) in helping students achieve a basic or foundational form of a pose that can be deemed “correct.” And many students view physical touch as a helpful learning tool to this end.

One student respondent told us that “I feel like as a new Yogi it helped immensely when I had a teacher assist/touch/correct me when I wasn't in a pose or doing a transition correctly (more safe). I felt the correction helped me find my correct postures and learn new ways my body moved or how it could be/feel in specific positions/poses I had not previously done.” Another student stated that “I feel like I'm not getting the best instruction I could be getting if the teacher isn't correcting me with physical touch. That's how I learned correct down dog, for example.”

On a related note, as a reason not to offer or receive touch, our survey found that yoga teachers were five times more likely than students to indicate they felt verbal and visual demonstrations were superior to physical touch. This suggests that while some teachers tend to view verbal and visual cues as superior to tactile ones for the purposes of learning, most students do not experience this same distinction.

These survey results suggest that physical touch may be a more helpful learning tool for students than yoga teachers realize. Teachers who feel comfortable offering touch in situations where they have consent may feel warranted in providing physical assists in addition to purely verbal and visual cues as a means for helping students (particularly newer ones) find the right positions in their poses.

Reasons Against Touch

Whereas yoga teachers and students agreed on 2 of the 7 possible reasons for touch, they did not agree on any of the 6 reasons not to touch. In fact, more than half of the students surveyed reported that there was no reason at all why they would not prefer to receive touch (which reflects what we know from Question 1 – that 74% like to be touched). By contrast, only 4% of teachers reported that there was no reason they would not provide touch.

This discrepancy is understandable considering the very different role that teachers and students play in the context of a yoga class. Students are mostly concerned with their own experience on their yoga mat, while teachers have the responsibility of creating a safe space among the entire group dynamic of their class. Additionally, teachers prioritize teaching techniques that they believe facilitate the most potential for student learning.

For example, over 60% of teachers cited “I want students to discover poses for themselves and not rely on me” as a reason not to touch students, while less than 10% of students chose this reason for not wanting touch. If students don’t find value in specifically discovering poses on their own without their teacher’s tactile help, is this a case for teachers offering more touch in this context? Or do teachers know better in terms of empowering their students’ sense of agency? In these cases, where students express the desire for physical assistance, if the teacher chooses not to touch, might it be helpful for the teacher to educate the student on their rationale for withholding that touch?

Teachers were also almost twice as likely as students to say that touch distracts students from their yoga practice. Is this another case of teachers possibly knowing better? (As a side note, couldn’t verbal cues distract students from their practice as well – just in a different way?)

It’s also interesting to note that teachers seem to be more afraid of injuring their students through physical touch (50%) than students are afraid of being injured by their teachers’ touch (20%). Does this suggest that students might trust their teachers more than teachers trust themselves?

Along similar lines, 18% of teachers reported not feeling qualified to offer physical touch, yet only 8% of students thought this about their teachers. So teachers might take this as a vote of confidence that their students view them as experts!

The #1 reason teachers reported for not offering touch was trauma sensitivity (72%). At the same time, only 12% of students cited a history of trauma as a reason they would not like to receive touch. The possibility of touching a student with past trauma who ends up feeling violated or re-triggered as a result is a very real and extremely negative one. Therefore, it makes sense that teachers would consider this an important reason not to touch.

And although only a small minority of students reported having a history of trauma, is it possible that this is partly because people with a history of trauma are less likely to practice yoga because they don’t feel that yoga classes are a safe space given the possibility that a teacher might be hands-on? Is the prevalence rate of people with a history of trauma higher in non-yogis?

If students have a clear and effective means of communicating their desire to receive or refuse touch (i.e. a consent practice), does this create a space in which touch can be offered in yoga appropriately and safely?

Consent Preferences and Practices

This survey did not reveal a strong preference reported by students for any one type of consent option. The most popular option was “verbal check in, first time taking class,” but only 38% of students said they preferred this method.

Surprisingly, consent cards ranked relatively low on the list for students (21% voted for this option), and only 1 in 9 teachers reported using consent cards in their class. Consent cards clearly aren’t the gold standard they are sometimes made out to be considering how infrequently teachers are using them. However, this might be fine since slightly more students prefer to provide consent verbally versus non-verbally.

“Verbal check in before every touch” was students’ second lowest choice (17%), although it was the highest vote for teachers (39%). Even though 17% is a relatively low percentage of students who want their teacher to check-in before every touch, does it make sense that the teacher cater to the “common denominator” in this regard? Is it a less serious infraction to ask for consent repeatedly (even when many students prefer not to be asked repeatedly) than not to ask for it when some students do want to be asked every time?

Given how widely the students’ preferences varied, it seems like in an ideal world the teacher would ask each student how they personally like to provide consent. But in a class setting with more than a few students, that’s likely not feasible. “A verbal check-in the first time a student takes their class” was in both groups’ top 3, so maybe that’s the best compromise? Even with that, though, only 38% of students’ preference would be matched.

In summary, our data show that students have a wide variety of different preferences for how they like to establish consent, so a variety of methods can “work.” If students feel strongly, they should feel empowered to share their preference for how to establish consent with their teacher.

Other Considerations

This survey reveals a clear mismatch between the percentage of students who like to receive touch and the percentage of teachers who consistently provide it. Although this mismatch can be partly explained by the reasons reported by teachers that we have already covered (trauma sensitivity, injury risk reduction, etc.), there are other potential reasons to avoid touch that are less socially desirable to admit, but may nevertheless be motivating factors as well. Examples of such reasons one teacher shared with us were not wanting to touch sweaty students’ bodies, touch requiring extra energy/work, and not wanting to expose oneself to potential germs.

While we didn't include such options in this survey, it's possible that additional reasons like these are also playing a role in the mismatch this survey points to.

Additionally, in many yoga settings, the nature of classes has taken on more of a mass market style in which an increasing culture of anonymity and less personal connection between yoga students and teachers has resulted. Consider the many yoga studios located in crowded markets that offer free or highly discounted monthly pass specials (i.e. through discount services like Groupon), which encourage students to "float around" from studio to studio as they wait for the next deal to be offered. Another example is the growing number of national chain yoga studios that offer scripted, unvarying classes and do not encourage original or innovative yoga teaching.

When we consider that (1) there may be more potential "downsides" for teachers to touch than were officially acknowledged in this survey, (2) yoga students often find themselves in relatively anonymous, superficial relationships with yoga teachers, and (3) yoga teaching itself is not known for being a particularly well-paying vocation (especially in more anonymous settings like large gym and yoga studio chains), it seems understandable that many yoga teachers would consider touching students a somewhat high-risk, low-reward scenario.

Further evidence on this front comes from the many teachers who responded to our survey and told us that while they do not touch students whom they do not know, they are more open to offering touch to students who come to their class regularly.

One takeaway suggestion for students who are desiring more touch, then, is to find teachers they like and build long-term, trusting relationships with them by attending their class over time. Students who like touch could even consider communicating with their regular teachers by expressing to them that touch is an offering they appreciate or thanking them when they do receive touch. (Positive reinforcement for the win!)

Things to Keep in Mind

The strengths of this survey are the large number of responses (931) and wide range of ages (21 to 74 year old) and years practicing (0 to 50). In addition, the open-ended section in which respondents shared additional thoughts enriched our quantitative data.

That said, the teachers and students who replied to this survey were a relatively homogenous group from a race, gender, and geographical standpoint (92% female, 86% white, 92% North American or European). Furthermore, apart from vinyasa (40%) and hatha (23%), no style of yoga had greater than 4% representation.

It’s important to point out that the respondents were not a random sample. About 88% of them were yoga teachers and students who follow Jenni, and the remainder came through colleagues’ sharing of the survey link on social media. We consider this a strength because our intention was to learn more about this specific yoga community and to share what we discovered with the members of this community.

Thus, it’s very possible that the yogis surveyed aren’t representative of all yogis – and that the results of the survey would differ in other samples. As such, care should be taken in generalizing our results to demographics and styles not well-represented in our sample, as well as to yogis whose approaches differ substantially from Jenni’s. We recommend that future surveys be conducted with diverse samples to further explore these issues.

Conclusion

All-in-all, our survey of 931 yoga students and teachers suggests that these two groups largely do not agree in their opinions on physical touch and consent in yoga. Whereas 74% of students “like” and “strongly like” receiving touch in yoga, only 19% of yoga teachers reported offering touch “always” or “often.” And only 10% of students dislike being touched, yet nearly half of teachers offer touch “rarely” or “never.”

Students and teachers did agree that increased body awareness and relaxation facilitation were two good reasons for teachers to touch students , but these were the only points they agreed on at all. For the other 5 possible reasons to offer touch, students wanted touch for each one of them more than teachers wanted to provide it.

When it came to reasons not to touch, students and teachers differed across the board. Teachers found all of the possible reasons not to touch significantly more important than students did, and over half of students (53%) reported no reason at all why they would not like to be touched.

So whose preferences should be followed: the teachers' or the students'? Does the teacher who rarely or never touches always know best, or should the possibility be open for the student ("the customer") to receive touch if they want it?

Trauma sensitivity was the most common reason that teachers reported for not offering touch (72%), with 12% of students citing a history of trauma as a reason they would not like to receive touch. Although those with trauma were in the minority, the extremely negative ramifications of unintentionally violating a student with past trauma by touching them justifies the high concern teachers have about this issue.

It is therefore essential that sound practices are in place to prevent students who do not like being touched from receiving touch. Is offering little-to-no-touch in yoga classes altogether the best practice for achieving this goal, considering the value that a high proportion of students place on this aspect of a yoga class?

If students had a clear, safe, and effective means of providing consent to be touched, would this allow the 10% who prefer no touch to be honored while keeping the possibility open for the 74% who prefer touch to receive it?

As far as consent goes, our survey results indicated no clear preference among students for one single consent style. This suggests that in private or small group settings, the best practice might be for teachers to ask students individually which method of consent they prefer. However, in larger group settings, this approach is most likely not feasible. Unfortunately, we don’t have a perfect answer here. We’d love to know what solutions you think of that might ensure that student preferences for consent practices are met.

Regardless of which method of consent is utilized, teachers should make it a priority to create a safe space for students to feel comfortable and supported in expressing their preferences. And yoga students should feel confident in communicating their desires with their teacher.

By keeping the lines of communication between students and teachers open, we can foster safe spaces and begin to reduce the mismatch between students’ preferences and teachers’ practices regarding physical touch. We hope the results of this survey provide a launch point for continued conversations.

For further reading, see 5 Influential Yogis Weigh in on Yoga Adjustments: When, Why, and Whether to Give Them

Travis Pollen, co-author: Travis Pollen is an author, personal trainer, and PhD candidate in Rehabilitation Sciences at Drexel University. His research focuses on core stability, movement screening, and injury risk appraisal in athletes. He also holds a master’s degree in Biomechanics and Movement Science along with an American record in Paralympic swimming. He’s been a yoga student for 15 years. Website | Instagram | Facebook